Shakespeare’s characters are woven into the texture of Western culture. They have taught us many lessons about human behaviour and we quote them all the time: we use things they said in our everyday speech, often without even realising it (catching a cold, break the ice, the naked truth, fancy free, with bated breath etc.). The most famous of Shakespeare’s characters are as familiar to us as the people we know and we almost think of them as real human beings. Of course, they are only literary character but Shakespeare has presented them with such “truth” that they act as models for a way of looking at life. So which are the characters that have the most influence on the way we think, some 400 years after Shakespeare’s death?

Hamlet, Hamlet

Hamlet is the most famous of Shakespeare’s characters – the one we most quote and the one we most refer to when thinking about human life and existence. His utterance ‘to be or not to be, that is the question’ is probably the most famous of all of Shakespeare’s lines, and the soliloquy that follows is a deep exploration of that great human theme – life and death. Hamlet also contemplates such issues as political corruption, marital fidelity, family, revenge motives, religion, and more. Hamlet’s deliberations have offered us food for thought for four centuries and whatever deep human dilemma we are confronted with the language to describe it is likely to have come from Hamlet’s mouth.

Juliet, Romeo & Juliet

Juliet emerges in our times as a strong female role model. The fourteen year-old displays remarkable strength, courage and fortitude. Such strength in a girl of her age may seem improbable but Shakespeare makes it work by giving her enormous passion and determination, and it’s convincing.

At her age she would have been in a high hormonal condition, in that her falling in love with Romeo is so sudden and intense. However, she is highly intelligent and, in spite of the turmoil of her emotions, able to think clearly and to accept the consequences of her impulsive actions. She exists in a social system in which a father demands loyalty and total obedience from a daughter and expects to receive it. In spite of all the threats and physical violence from her father she adamantly refuses to marry the man her father has selected as her husband. It is a great battle as he has chosen Paris for his own social advancement and she has refused. What Capulet doesn’t know is that she is in love with someone else, and has secretly married him, but not only that, he is a member of a family with which his family is conducting an ancient feud. In trying to find a way out of this impossible situation she agrees to Friar Lawrence’s scheme to take a drug that will make her appear to be dead, after which she will be woken by Romeo and run away with him. It’s a terrifying prospect as she knows she is going to wake up in a tomb full of skeletons and rotting corpses. In spite of being terrified she takes the drug. It’s an act of great faith and commitment.

Juliet is remarkably like a twenty-first century western woman in her defiance of the restraints that bind her. She has rightly become, not only Shakespeare’s most famous female character, but one of his greatest characters and one we can look up to and learn from her.

Lear, King Lear

Lear is the main protagonist in King Lear. Often referred to as Shakespeare’s greatest play, King Lear’s scope is huge. One of its main thrusts, however, is the theme of authority and responsibility. Lear decides to pass on all his lands and interests to his daughters and retire. He tells them, though, that he will retain the title of king, and soon discovers that the title is meaningless without the power and authority behind it. He ends up mad and completely naked in the wilderness but he eventually comes round with an understanding of that principle.

A parallel main protagonist is the Duke of Gloucester. Gloucester is also deposed by Lear’s children. His eyes are gouged and he’s blinded. He eventually discovers that eyesight can get in the way of actually ‘seeing’ in the deeper sense. He says “I stumbled when I saw.’ This is something that Lear also discovers, in the figurative sense.

At the centre of the drama are two naked men, together on a blasted heath. Both are naked: one is a king the other a beggar. They are both mad, although the beggar is one of Gloucester’s sons, not mad but disguised as a beggar and pretending to be mad. That central drama draws attention to the fact that if you remove all clothing – the king’s expensive gown and the beggar’s rags – one can’t tell which is the beggar and which the king. The idea of that is that being a king is not just to do with titles and fine gowns and material possessions; it’s much more to do with something else, something not to do with outward signs, that makes a man a king. One should be able to recognise a king, not by his trappings and kingly garments, but by something within him. Later, when Lear comes out of his mental confusion he understands that, and understanding that, describes himself as ‘every inch a king.’

The play teaches us many things and has several lessons for human beings of all the ages following Shakespeare’s, and into the future. The play illuminates the nature of the bond between parent and child and explores loyalty, among several other themes. If we want to understand politics and the importance of integrity in the political world, if we want to understand the realities of power and authority and the responsibilities of authority we should pay attention to the experience of Lear as presented by Shakespeare. The lessons are as true and valid today as they were four hundred years ago.

Macbeth, Macbeth

Macbeth is an example of the proposition of famous twentieth century British politician, Enoch Powell, that “all political lives, unless they are cut off in midstream at a happy juncture, end in failure, because that is the nature of politics and of human affairs.” Four hundred years before Powell said that Shakespeare had illustrated it in the political career of Macbeth.

When we first see Macbeth he is Scotland’s greatest national hero. He is not only one of the main nobles but also King Duncan’s military general. We see him fearlessly taking on the rebels in an uprising against Duncan and we see the adoration he gets from everyone, including the king. In the play Scotland has an elected monarchy, the king elected by the noblemen. Macbeth knows that if there were an election for king he would easily win it. He gets the idea that he could be king if only Duncan were out of the way. Egged on by his wife, Lady Macbeth, he decides to murder Duncan. He goes ahead with it and is immediately wracked by a paralysing sense of guilt. Even before he is elected his support is draining away and for most of the rest of the play he fights to maintain his position as king. He begins murdering his opponents and goes even as far as slaughtering the whole family of his main opponent, Macduff. Shakespeare depicts the murder of one of the Macduff children onstage, and we witness at first hand the savagery into which Macbeth has descended. What we are seeing in the play’s action is the transformation of someone from a noble, heroic, loyal man into a depraved and reckless killer because of his own corruption.

The transformation is brought about by Macbeth’s ‘overweening’ ambition to be king and his inability to manage the consequences of the action he has taken to achieve that. Some politicians advance fairly cleanly to positions of power and others do it in unacceptable ways. We frequently see the latter, once they are in power, struggling to stay in power, having to fight off the repercussions of the corrupt acts they have committed to gain it. That paralyses their ability to function. Eventually, as their increasingly desperate acts catch up with them, their careers suffer an ignoble demise.

In Macbeth’s case a rebel force headed by Macduff acts against him and he ends up being decapitated. We see this pattern in modern politics and there have been cases where cover-ups – desperate measures to stay in power – have brought powerful figures down. Shakespeare had thought about all that four hundred years ago, and any politician contemplating achieving and retaining power by foul means should take note of Macbeth’s experience. But not only those using extreme means: Powell was talking about all political careers because as those careers advance politicians are drawn into things that make their success increasingly difficult and, as Powell would have it, impossible.

King Henry V (Prince Hal)

Henry, son of King Henry IV, known as Hal, appears in three plays, first as the prince, in Henry IV Part 1 and Henry IV Part 2, and as king in Henry V.

This sequence of plays begins with Hal as the rebellious teenage son of King Henry V, the rebel who has usurped the divinely ordained King Richard II. Richard Bolingbroke, now King Henry, is having difficulty in functioning as king in spite of the support he had in deposing King Richard. His eldest son is not co-operating, spending his time in London pubs, surrounded by a bunch of disreputables. The first play in the sequence is a delightful story with several comic scenes with the young prince interacting with ordinary people, immersing himself in their activities, some of them even criminal, with lots of eating and drinking involved. Among his companions there are prostitutes, thieves, drunkards and swindlers.

The idea behind that is the question of what makes a good king. How should a king be educated to enable him to respond to his people? We live in an age of Western democracies but there are still many countries that are ruled by single authoritarian figures. That was the case in Mediaeval England and the king had huge authority tempered, however by the need to maintain the support of other powerful men. He also needed the support of the people to avoid rebellions and effectively to conduct wars.

Hal is frequently reprimanded by his father for his dissolute lifestyle but eventually, at a time of his own choosing, he returns to the fold and shows himself to be a courageous and effective support to his father. On Henry’s death Hal becomes king and the third play is all about what a good, wise and effective king he is. Something particularly striking is his consideration for the ordinary people in his kingdom and he becomes very much, interacting with his soldiers, for example, a very popular and effective king.

This is one of Shakespeare’s explorations of leadership. It’s almost a plea for the democratic principle, centuries before democracy became part of the country Shakespeare inhabited. There are lessons in Hal’s journey for all leaders.

Iago, Othello

In Iago, one of Othello’s officers, Shakespeare offers us a character whose psychological pattern was only recognised as a personality defect four hundred years later. Iago delights in the pain and ultimate destruction of others. He has no real reason for engineering that other than for his own gratification. He is highly intelligent, an expert in manipulation, unfeeling and remorseless, and although cunning, he is reckless.

In 1998 Robert D Hare, professor emeritus of the University of British Columbia, Canada, a researcher into psychopathy, produced his renowned Hare Psychopathy Checklist, ten points one can use to diagnose psychopathy. A psychopath is traditionally defined as a person who has a personality disorder characterised by persistent anti-social behaviour, impaired empathy and lack of remorse and who exhibits disinhibited egotistical traits.

If professor Hare had examined Iago and made a diagnosis he would probably have declared him a psychopath. Among his ten points are: lack of remorse or guilt; superficial emotional responsiveness, callousness and lack of empathy; impulsivity; irresponsibility and criminal versatility. Iago demonstrates all those traits. There have always been psychopaths around us and it is a mark of Shakespeare’s deep insight into and keen observation of human behaviour that one of his major characters is so accurately depicted as a psychopath. It was only in the twentieth century that psychopaths became the subject of scientific study, but here was Shakespeare, four hundred years before that, giving us the perfect depiction of a psychopath – one who matches the profile of psychopaths like Ted Bundy who have been comprehensively studied.

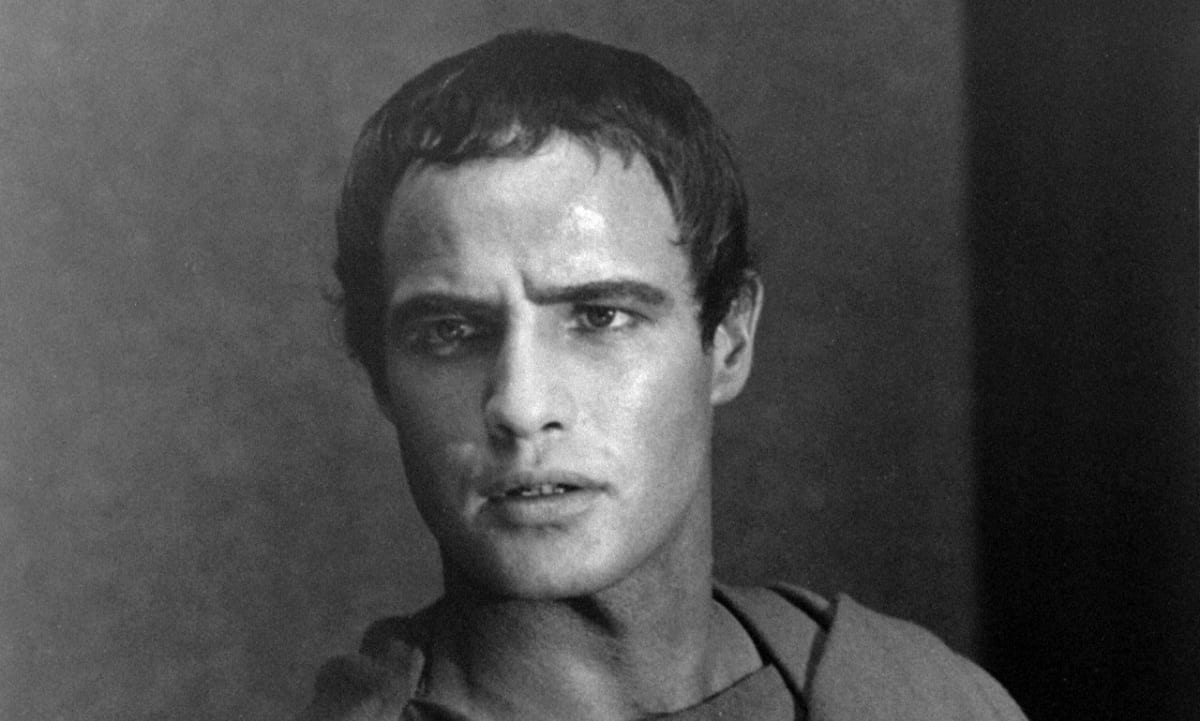

Kenneth Branagh as Iago

Antony, Antony & Cleopatra

In Antony and Cleopatra Shakespeare addresses one of his major themes – political power. There are many lessons for those conflicted between their powerful public positions and their private lives.

After defeating Caesar’s assassins in a major battle depicted in Julius Caesar, Antony assumes the leadership of Rome together with his fellow generals, Octavius Caesar and Lepidus. On a visit to Egypt, a Roman satellite, Antony falls in love with the Egyptian queen, Cleopatra. During their love affair he falls increasingly under her spell and continuously postpones his return to Rome, and neglects his responsibilities there. He is anguished by that but is unable to resist the queen. The two cultures are very different. The Roman ethic is hard and matter-of-fact, rigid and masculine. Egypt is softer, feminine, more relaxed and fun. Antony becomes a part of that world but deeply conflicted by his understanding that he is avoiding his responsibilities.

His experience in Egypt is life changing for him. It is a spiritual journey in which the world of politics drifts away from him. Renowned as a great military general, he is swiftly becoming a man undergoing a spiritual journey that takes him away from that. When eventually confronted with the Roman forces he chooses to engage with them on the sea rather than with a land army. By doing so he places himself completely out of his comfort zone. Indeed, when Cleopatra withdraws from the sea battle, turns her ship around and sails away, he abandons the battle and follows her, and is defeated. At this point he has changed from a man of war and politics to a man transformed through the power of love, for whom power is meaningless.

History has many examples of powerful political men and women who have looked more deeply into life beneath the superficial practice of politics. Sometimes it is by means of study, sometimes by going to prison for crimes rooted in their political activities, and sometimes through love. In Antony, Shakespeare has shown us the mechanics of that process.

Beatrice, Much Ado About Nothing

Much Ado About Nothing is a remarkable play that combines a borrowed ancient tale with a modern story entirely invented by Shakespeare. The character that stands out of Shakespeare’s invention is Beatrice who is the prototype of the modern feminist woman.

What is striking about Beatrice is her sparkling intelligence, her use of sharp, punchy language and her fierce sense of independence. She is an attractive young woman who is very sceptical about men and is determined never to marry. When some officers arrive on a visit to her uncle’s house, where she is living, she encounters the young Benedick, who also scorns marriage. She already knows him and claims not to like him because she regards him as a typical, bragging male. They immediately engage in fast, witty repartee in which they light-heartedly insult each other, using derogatory nicknames about each other. Their friends are determined to match them, however and trick them by engineering situations in which they overhear contrived conversations about how each one, respectively, fancies the other. The result is that they actually come together. During that process, though, Shakespeare explores the differences between male and female regarding the romantic make-up of the genders.

Watching them and listening to their conversations the modern audience is struck by how nothing has changed. Men and women do fall in love all the time and commit themselves to each other but each gender finds the other strange and unfathomable. It is partly sexual attraction that overcomes that and Shakespeare shows us that in this play. The power of attraction is so strong that they go into relationships in spite of the mystery that each one presents to the other.

Shakespeare’s spot-on analysis makes that recognisable to all of us. Beatrice exists in a Renaissance society in which women were not educated. It is clear, though, that Shakespeare makes her an educated young woman and we can easily believe that she has insisted on that from early childhood. She is well informed and ready to speak on any subject. She is also outspoken, in contrast to her cousin, Hero, who is very much a young woman trapped in that society’s norms regarding women. The men who dominate the household are in despair about Beatrice but are unable to control her. How an Elizabethan audience would have regarded her is difficult to fathom but to a modern audience she is the model for fully liberated, advanced twenty-first century women.

Edmund, King Lear

Edmund, the illegitimate son of the Duke of Gloucester in King Lear, is often regarded as one of Shakespeare’s villains, but it is not such a simple matter because Shakespeare develops him as a character in such a way as to allow us to see his point of view. Edmund justifies his actions and takes us with him.

Although he is Gloucester’s first son he has no rights to the succession. His younger brother, Edgar, is legitimate and is therefore his father’s heir. Edmund has a famous soliloquy in which he questions the convention that it is only if you are born in wedlock you have those rights. He points out that he is just as physically well-developed as his brother and just as intelligent and so it’s unreasonable to discriminate between them and to brand him as a bastard. He ends with the cry, ‘Now, gods, stand up for bastards!’

This play is very much about the conflict between the mediaeval world in which social structures are fixed by God and there’s no way around that, and the developing Renaissance humanism in which the emphasis moves away from God-centred to human being-centred, thus the Renaissance art – sculptures and paintings – that emphasise the beauty of the human body, realistically depicted in those works. Edmund is the literary equivalent of those Renaissance art works.

As a result of Edmund’s rejection, he turns against his father and brother and joins the daughters of Lear in their actions against Gloucester and Lear.

Although Edmund’s actions are unacceptable they can be seen as a fight-back in the way, in some countries in our modern world, the fight for equality goes on. We need only think about the Suffragettes, who smashed windows and engaged in other acts of sabotage in their campaign for the female franchise. One can point to many other actions against the establishment in the cause of equality. One can also see the justice of Edmund’s case in that in the twenty-first century the concept of illegitimacy his either disappeared or has no implications. The humanist principle, that it is the human being that counts and that every human being is as valuable as any other, is a fixed principle in modern Western democracies.

Across the four centuries since Edmund first appeared on a stage he has been interpreted differently in each generation. But in our age he is certainly a model for those offended by the principle of inequality based on such things as race, gender, or any condition determined by one’s birth.

Shylock, The Merchant of Venice

Shylock is often listed among Shakespeare’s villains and the play is sometimes condemned as anti-Semitic. Both are failures to read the play accurately. Shakespeare himself has been called anti-Semitic by some but that, too, is inaccurate. Apart from the impossibility of reading Shakespeare’s mind to understand what he thought about things, his presentation of a Jew is simply an exploration of what it means to be a Jew living in a Renaissance Christian society. As he always does, Shakespeare explores the human condition with honesty and truthfulness. In this case he is exploring the conditions of a Jew in Elizabethan England. Although the play is set in Venice Shakespeare’s plays always address the issues of the England of his time.

In this play Shakespeare depicts the Christian characters and their culture as thoroughly nasty. He does that mainly by showing their attitude to, and treatment of, the Venetian Jews. The Elizabethan audience will not have encountered many Jews but they will have had strong prejudices against them. They will easily have believed that Jews are money-grabbing, stand-offish and hostile. In The Merchant of Venice Shakespeare presents the typical Elizabethan view by bringing a Jew into the middle of a Christian community, and exploring the effect.

Shylock is a wealthy money-lender. He will deal with anyone but he will not eat, drink, socialise or pray with Christians. That is partly because his religion would be opposed to that but it is also because he is angry about the injustice of the way he and his community are being treated by the mainstream society. When the merchant, Antonio, is in trouble because his ships have gone missing, he is desperate and, very much against his inclinations, he approaches Shylock for a loan. Shylock agrees to it and waives the interest on the money and suggests, instead, that if Antonio fails to pay his debt that he will give Shylock a pound of his flesh. Antonio, not taking him seriously, agrees. Shylock has no way of knowing whether Antonio’s ships will return or not. During the transaction he is badmouthed and insulted by Antonio and his friends, which is the normal way the Christians talk to Jews.

By the time Antonio defaults on his debt Shylock’s daughter, Jessica, has been abducted by her secret Christian lover and his friends and that has broken broken her father’s heart. He has revenge on his mind. In that context he now goes to court to get his pound of flesh. Having gone too far by insisting on it, he is severely punished by a court heavily biased in favour of the Christian community.

Shakespeare shows us all this. A careful reading of the play shows the nastiness of the Christians. Shakespeare disguises that by depicting them as good and kind people among themselves He shows Shylock as quite mean-minded and having different, alien values, so we can quite easily fall into the trap of thinking Shakespeare has been anti-Semitic but if we look at the treatment of Shylock it is quite clear as to what Shakespeare is doing.

Shakespeare gives Shylock a speech that will stand for all time as a plea for all those who are discriminated against on the grounds of race, religion, gender, or anything else and as we read that we can apply it universally, to all those situations and to all times. In the twentieth century, though, only the most advanced societies apply the logic of that speech while many more countries have a long way to go to catch up with Shakespeare.

Here is a part of that speech:

‘I am a Jew. Hath

not a Jew eyes? hath not a Jew hands, organs,

dimensions, senses, affections, passions? fed with

the same food, hurt with the same weapons, subject

to the same diseases, healed by the same means,

warmed and cooled by the same winter and summer, as

a Christian is? If you prick us, do we not bleed?

if you tickle us, do we not laugh? if you poison

us, do we not die?’