John of Gaunt appears as a central character in Shakespeare’s play, Richard II. As a character in a play he’s not all that interesting, but his political decisions, and his death, are major dramatic devices.

John of Gaunt in history

John of Gaunt, who came by the unusual name “Gaunt” as a result of the corruption of the name John of Ghent, was the Duke of Lancaster. He lived from 1340 to 1399, during which time England was jolted by a major regime change, when his nephew, King Richard II was dethroned by Gaunt’s son, Henry Bolingbroke, who became King Henry IV, making John of Gaunt the grandfather of the great English king, Henry V. He was the father of the Royal House of Lancaster, and the third son of Edward III, immensely rich and hugely influential.

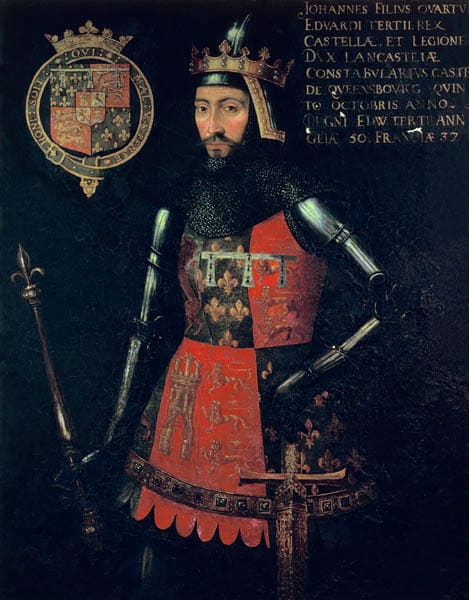

A portrait of John of Gaunt commissioned by Sir Edward Hoby in 1593

John of Gaunt’s role in Richard II

When we first see Gaunt in Shakespeare’s Richard II play, he seems to be just another of the courtiers flattering King Richard, and allowing him to get away with his misdeeds and general bad behaviour. He even turns a blind eye to Richard’s part in the murder of his brother, Thomas of Woodstock.

Believing strongly in the concept of the divine right of kings – that God has chosen the monarch and human beings just have to accept that – he even advises Richard to exile his own son, Henry Bolingbroke, when Bolingbroke accuses Mowbray of being a traitor. However, things begin to change as Gaunt starts to suffer emotional pain from the conflict of his duty as a loyal subject on the one hand and a father on the other.

His response to that emotional conflict is that he tries to be both. Regretting his previous sycophancy he starts to give the king real advice: he tells his nephew frankly that he is a bad king. It is too late though. Richard ignores his advice to restore his cousin and that leads to Bolingbroke getting up an army and returning from France, overthrowing Richard, and announcing himself as King Henry IV.

The death of John of Gaunt

John of Gaunt’s death is a major dramatic device, and the story takes a new direction at that point. His death sets several important strands going in the play. The first is that Richard takes the opportunity to seize his uncle’s lands. For Bolingbroke, smouldering away in France, while also believing in the divine right of kings, this is too much. In stealing his birthright Richard has gone too far. Bolingbroke returns to England and, while not seeking to depose Richard, but just to get his father’s lands returned, events begin to snowball and he eventually comes to the decision to throw his cousin out and take the crown for himself. Which he does. By doing so, he changes the course of history. Being a usurper, he is unable to rule effectively, and can only struggle on, On his death the usurper problem evaporates and his son inherits the throne as King Henry the V (Harry of England) and becomes the most popular English king, both in history and in Shakespeare’s plays.

John of Gaunt’s “Sceptered isle” speech

John of Gaunt’s big contribution to English literature is one of the most quoted speeches in all of Shakespeare, and the definitive collection of patriotic tributes to England. In Act 2, Scene 1 of Richard II he expresses both the exceptional beauty of the land he loves and his feelings about it:

This royal throne of kings, this scepter’d isle,

This earth of majesty, this seat of Mars,

This other Eden, demi-paradise,

This fortress built by Nature for herself

Against infection and the hand of war,

This happy breed of men, this little world,

This precious stone set in the silver sea,

Which serves it in the office of a wall,

Or as a moat defensive to a house,

Against the envy of less happier lands,

This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England,

This nurse, this teeming womb of royal kings,

Fear’d by their breed and famous by their birth,

Renowned for their deeds as far from home,

For Christian service and true chivalry,

As is the sepulchre in stubborn Jewry,

Of the world’s ransom, blessed Mary’s Son,

This land of such dear souls, this dear dear land,

Dear for her reputation through the world,

Is now leased out, I die pronouncing it,

Like to a tenement or pelting farm:

England, bound in with the triumphant sea

Whose rocky shore beats back the envious siege

Of watery Neptune, is now bound in with shame,

With inky blots and rotten parchment bonds:

That England, that was wont to conquer others,

Hath made a shameful conquest of itself.

Ah, would the scandal vanish with my life,

How happy then were my ensuing death!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!