Contrary to popular belief, Shakespeare did not write in Old or Early English. Shakespeare’s language was actually Early Modern English, also known as Elizabethan English – much of which is still in use today.

Old English, Middle English, Modern English

Before exploring the wonderful depths of Shakespeare’s English, it is important to understand what exactly Old, Middle, and Modern English are and when they were/are spoken.

Old English is the earliest recorded form of the English language. It was spoken throughout England as well as in parts of Scotland in the early Middle Ages. It first came to Great Britain by Anglo-Saxon settlers in the 5th century. The first recorded Old English writing comes from the middle of the 7th century.

The Old English period ended after the Norman Conquest of 1066. With the growing influence of Anglo-Norman, the language evolved into what is known today as Middle English.

Here is an example of Old English (of which there were four distinct dialects):

Fæder ure þu þe eart on heofonum; Si þin nama gehalgod to becume þin rice gewurþe ðin willa on eorðan swa swa on heofonum.

These are the first lines of The Lord’s Prayer in Old English. With just a glance at the text, it’s obvious how different this English is from the Modern English spoken today and in Shakespeare’s time.

Here is an example of the same passage in Middle English:

Oure fadir that art in heuenes, halewid be thi name; thi kyndoom come to; be thi wille don in erthe as in heuene.

In the 14th century, after the Great Vowel Shift (a series of changes in pronunciation), that Early Modern English, or New English, came into being.

Here is how the lines would’ve been written when Early Modern English was first becoming the standard in Shakespeare’s time:

Our father which art in heauen, hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdome come. Thy will be done, in earth, as it is in heauen.

This is very different to Old or Middle English, but not too different to today’s English, right?

Shakespeare’s English

The Early Modern English language was around 100 years old when Shakespeare was writing his plays. All major documents were still written in Latin, and over the course of his lifetime, Shakespeare contributed approximately 1,700 to 3,000 words to the English language.

Shakespeare had an immense vocabulary that stretches to four times that of the average well-educated man by some records. His version of English was spoken and written until around 1690, when it shifted into what is fully recognizable today as Modern English.

Take a look at this famous passage of Shakespeare’s language from Romeo and Juliet:

If I profane with my unworthiest hand

This holy shrine, the gentle fine is this:

My lips, two blushing pilgrims, ready stand

To smooth that rough touch with a tender kiss.

In these lines, Romeo Montague is talking to Juliet Capulet, professing his desire to kiss her while at the same time comparing his lips, through a metaphor, to “pilgrims.”

Shakespeare’s use of language goes beyond simple storytelling. His works have endured because of the creative, never before seen ways that be combined words and used figurative language. Take a look at Juliet’s response:

Good pilgrim, you do wrong your hand too much,

Which mannerly devotion shows in this;

For saints have hands that pilgrims’ hands do touch,

And palm to palm is holy palmers’ kiss.

Shakespeare uses puns, similes, metaphors, and allusions all within this section of the play. It is one of three sonnets embedded in Romeo and Juliet and is one that is most evocative. He manages to convey Romeo’s interest, his concern that his advances are too forward as well as Juliet’s innocent, and yet flirtatious, perceptive.

Here is one more quote from the play, from Act III Scene 2:

O serpent heart hid with a flowering face!

Did ever a dragon keep so fair a cave?

Beautiful tyrant, feind angelical, dove feather raven, wolvish-ravening lamb! Despised substance of devinest show, just opposite to what thou justly seemest – A dammed saint, an honourable villain!

Juliet speaks these lines as a reaction to the news that Romeo killed her cousin Tybalt. She’s at once outraged and confused. Shakespeare uses oxymorons when Juliet calls Romeo a “feind angelical” (fiendish angel) and a “Beautiful tyrant.” He’s shown a side of himself that surprised her. In conclusion, Juliet marvels that his body, which she calls a “gorgeous palace,” could hold “deceit” or evil.

This is one of the best short passages to read when considering how Shakespeare used language. It shows the similarities and differences in Early Modern English and Modern English that is spoken today. At the same time, it also shows his skill with language, something that can’t ever be overstated.

Prose and Verse in Shakespeare’s Plays

The previous passage is an example of prose dialogue, something that Shakespeare’s characters often speak in. There is no rhyme or meter in the lines.

There are moments in which Shakespeare shifts into verse to write dialogue though. This is usually when a member of the upper class, or a noble, is talking. He uses blank verse or unrhymed iambic pentameter. This refers to the number of beats per line and the arrangement of the stresses. An iamb is one metrical foot. It contains two beats, the first of which is unstressed and the second stressed. When a line is in iambic pentameter, it contains five of these metrical feet.

Sometimes Shakespeare would use another technique, known as syncope, to remove vowels and change the pronunciation of words to fit in the pattern. For example, these lines from A Midsummer Nights’ Dream, spoken by Oberon:

Fetch me that flow’r; the herb I showed thee once:

In these lines, the word “flower” is pronounced with a single syllable.

Rarely, Shakespeare used something known as trochaic verse. This metrical pattern appears in “magical” passages, such as in Macbeth when the three witches transition into trochaic tetrameter for these famous lines:

Double, double toil and trouble,

Fire burn, and cauldron bubble

This helps emphasize their otherworldliness, the fact that these women are quite different from any of the other characters in the play.

Original pronunciation of Shakespeare’s language

There’s another angle to explore when considering Shakespeare’s language, and that is pronunciation.

These days when we see Shakespeare performed it tends to be full of weight and reverence – posh, and as fancy as the Queen. But there is another school of thought called “original pronunciation” (also known as “OP” or “Shakespeare’s pronunciation”). This is the concept of understanding, performing or listening to Shakespeare’s works (and language) as they would have been spoken during Shakespeare’s time

Here’s a fun video from Shakespeare’s Birthplace Trust that illustrates the difference between original pronunciation and received pronunciation:

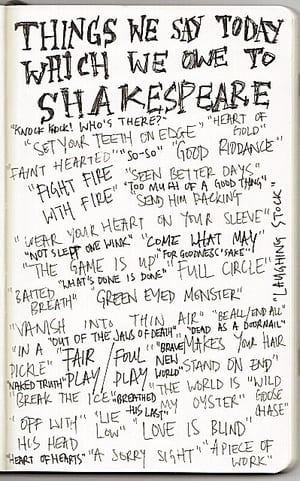

Some memorable phrases from Shakespeare’s language

That’s our take on Shakespeare’s language – what did you think, any questions? Let us know in the comments section below!

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!