When we talk in English or write anything in English we do not say that we are using ‘modern’ or ‘contemporary’ or ‘twenty-first century’ English. However, in two hundred years from now English speakers will look at the language we use and perhaps refer to it as something like ‘pre-contemporary’ English or give it some other label. The speakers in that time may have difficulty with some of the words we use, which will perhaps have fallen into disuse.

The spelling, too, may be different, and it may be that many words and sayings will require interpretation. And thousands of words will have been added to the vocabulary. Just think about it. Even in your lifetime you can point to new words that are absolutely legitimate, for example, ‘google’ used as a verb – to google something – and ‘selfie’ a 2014 entry to the Oxford English dictionary.

The pressures on our language are enormous. With blogging taking over from the printed media, with young people using the abbreviations of tweeting and texting (the single letter ‘u’ taking over from the full ‘you’), with the English language becoming a universal language and being infused with words and constructions from the scores of cultures that use it, in two hundred years English will undoubtedly be much changed.

There have always been pressures on the English language. The people who speak it don’t notice it changing, and if they do, they often complain about the changes and some of them try, in their own lives, to halt it – for example, those who fume against the abbreviations like ‘u’ and ‘luv.’ But it has been changing slowly and steadily for centuries and will continue to do so. There is nothing any individual can do about it. Those who lived in the times of what we call Old English and Middle English were, without knowing it, transforming the language as they wrote and spoke. That continuous process has brought us to what we call Modern English, the English we use today.

Look at this passage. What do you make of it?

‘Soþlice on þam dagum wæs geworden gebod fram þam casere augusto. þæt eall ymbehwyrft wære tomearcod.’

Probably not much. What about this one?

‘Forsoþe it is don, in þo daȝis a maundement wente out fro cesar august, þat al þe world shulde ben discriued.’

You will probably have recognised one or two of the words there. And the next?

‘And it came to passe in those dayes, that there went out a decree from Caesar Augustus, that all the world should be taxed.’

You will fully understand that one, although the spelling is a bit ‘wrong’ and it sounds a bit ‘ancient’. But it is very close to the way we write today and almost identical to English as we speak it.

The next one is entirely comfortable. It’s the way we speak and write today.

‘In those days Caesar Augustus issued a decree that a census should be taken of the entire Roman world.’

Now you recognise the sentence: it’s from the Gospel of Luke.

The first passage is in what we call Old English. We cannot understand it unless we learn it as we might Latin or Ancient Greek. That is the way the English spoke and wrote at a particular time in the first millennium. Some of the most famous literary works of the time are ‘Beowulf’ and ‘Sir Gawain and the Green Knight.’

The second is what we have labelled Middle English. Without any lessons, you can recognise some words. You can make out ‘went out from Caesar’ and ‘all the world.’ That is the language of Chaucer which, if not easy to understand, is not impossible if one concentrates.

The third passage has few differences from Modern English. It is what is known as Early Modern English, the language in which all of Shakespeare’s plays and poems and those of his Elizabethan and Jacobean contemporaries wrote. It is also the language of the King James Bible.

Compare the first passage with the last. There was no revolution, no law passed to change the language. The people living in England just spoke and wrote and the final passage is where it has ended up, although ‘ended up’ is inaccurate: it would be better to say that that is where written English is at this moment.

But even so, take the English of England and the English of America, Ireland, Scotland, Canada, South Africa, Australia, and so on. There are differences between them although they are all lumped together as ‘Modern English.’

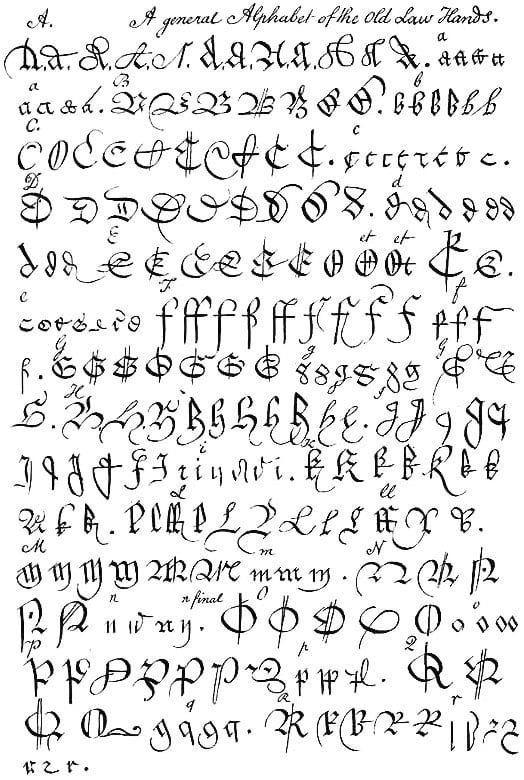

Old, middle, and early modern English letters

The main thing about Early Modern English is that it was an early version of Modern English and is accessible to all of us. The differences between the two are mainly the loss or change in meaning in Modern English of some words that were common in Early Modern English.

The label ‘Early Modern English’ embraces quite a long period in history. William Caxton, the man who introduced printing to England, printed a prose work about the Arthurian Legends by Sir Thomas Mallory in 1485. ‘Le Morte d’ Arthur’ is generally classified as an Early Modern English text. It is at the early end of the time scale of which Shakespeare and his contemporaries are at the later end. Look at this example of the text:

‘And at the feste of pentecost alle maner of men assayed to pulle at the swerde that wold assay / but none myghte preuaille but Arthur / and pulled it oute afore all the lordes and comyns that were there / wherfore alle the comyns cryed at ones we wille haue Arthur vnto our kyng we wille put hym nomore in delay / for we alle see that it is goddes wille that he shalle be our kynge.’

If one were to modernise the spelling and punctuation that passage would be entirely accessible, and is accessible with just making an allowance for those technical aspects.

It is interesting to reflect on the fact that Caxton printed Chaucer’s Middle English text ‘The Canterbury Tales’ in 1476 and 1483 – working on them at about the same time as he was working on Malory’s text. Caxton was printing books at a time when the English language was changing very fast.

English has a tendency to simplify itself as time passes. Unlike modern German it has dropped gender signifiers, unnecessary prefixes and suffixes, and so on. Whereas French still uses the formal and familiar forms of address – ‘vous’ and ‘tu’, modern English has dropped that and uses only ‘you.’

Early Modern English those forms of address as ‘thee’ and ‘you’ but the picture is somewhat confused, the two forms often being used indiscriminately by Elizabethan writers. They are still a useful device, though, mainly to indicate insults. For example, to address a king or a high lord as ‘thee’ would be deeply insulting. When it comes to the King James Bible, however – a late Early Modern English text – God is addressed in the familiar form – ‘Our father, who art in heaven, hallowed be ‘thy’ name,’ ‘My God, my God, why has ‘thou’ forsaken me?’ The translators of that text were using only the one form for high and low, as we do today. They make Jesus address ordinary people with the same familiar pronoun with which he addresses God: ‘take up ‘thy’ bed and walk.’

Modern English has just the one pronoun – ‘you.’ Somewhere along the line English has switched from the single ‘thee’ to the single ‘you’ but even here, ‘thee’ is still used in some English-speaking communities.

The main thing to understand about Early Modern English, then, is that it is nothing but a label to describe the place where English was during the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries.

this is rubish

Thou sayest welle.

Thou giveth mine and my own (might not be doing that one right lol) a joyful folic though the past. ^-^