The three great themes of life – love, death and war – are also the three great themes of literature and, once again, Shakespeare leads the field: his plays are full of death and the exploration of death. Almost every way of dying imaginable occurs in the plays and, as usual with Shakespeare, it is (almost!) never gratuitous but always an integral part of the plot and ideas of the play. The deaths may be tragic, many are gruesome and violent, and others are just creative but they all move the play along towards the resolution of the play’s conflict.

The many plagues which decimated England and Europe in Shakespeare’s time helped shape a culture in which death was an ever-present force in daily life: images of corpses and skeletons abound in the art of the 14th and 15th centuries. In an era with high mortality rates, mass deaths due to disease, and little knowledge of medicine and hygiene, death was a mystery. Whole towns could be wiped out for no reason that anyone could understand and so death was considered the punishment of God.

The prevalence of incidences of death and the imagery of death in Renaissance art was a vital part of society’s attempt to comprehend a very real danger, to work through it, to explore it. And, of course, the playwrights made it exciting by exploring ways of dying as well, and in doing so, pandering to the audience’s taste for violence by presenting dying in gruesome ways. Elizabethan drama and Jacobean drama was especially gruesome, notorious for on-stage deaths. All of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, including Christopher Marlowe and Ben Jonson, wrote violent scenes that can still turn our stomachs. As the 16th century gave way to the 17th the younger dramatists were competing with each other to produce increasingly gory death scenes.

Suicide is always surrounded by dramatic circumstances and so, perfect for the theatre. There are more than twenty suicides in Shakespeare’s plays (thirteen explicit, and many more implied offstage), committed in the different circumstances that one may find in life, and each one contributes to the meaning of the play in which it occurs. At least seven are depicted as being admirable in their context. Four suicides are assisted, and at least three others are imitative. In most cases Shakespeare presents suicide sympathetically and, rather than reproach a character, the audience is left with a mixture of pity and admiration for the victim.

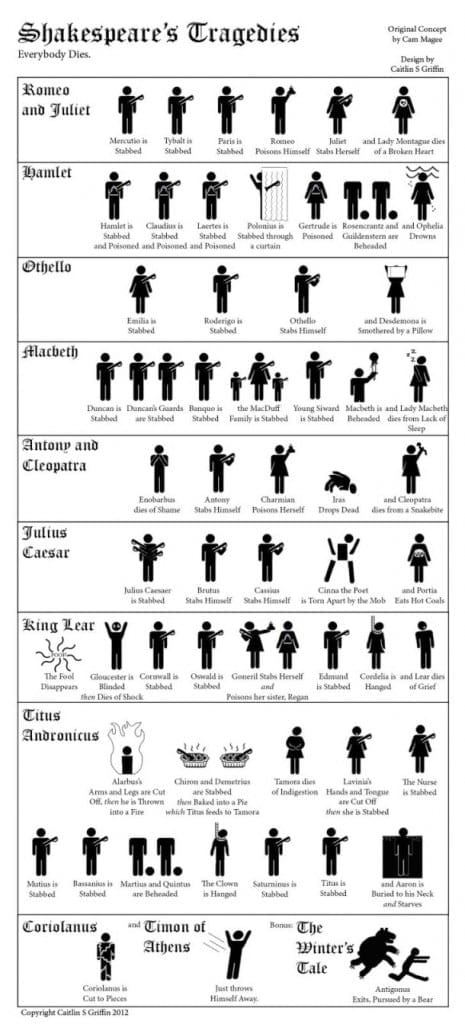

The causes of death in Shakespeare’s plays are numerous. Almost half the characters who die are stabbed; the next largest group are beheaded, and the next poisoned. Several characters die of shame and quite a few are hanged. Some die of grief and one of insomnia. One is torn apart by a mob, one eaten by a bear, one baked in a pie, one is bitten by a snake and one even dies of indigestion.

It may be useful to take one play to illustrate this theme: Shakespeare’s work at its best. In Hamlet Shakespeare explores several main ideas – family, corruption, revenge, and many others – but there is a sense in which the play is about death. Shakespeare explores death in every aspect of the text, and from every angle. The theme permeates the text and is portrayed in images that occur in almost every line, and in every scene. This play, Shakespeare’s most famous, deals so fully with this universal theme that it could never become dated. Death will always be human kind’s greatest and most fascinating mystery and for that reason Hamlet, four hundred years after it was penned, will remain fresh to each generation.

Death is present from the appearance of the ghost at the beginning of the play to the bloodbath in its closing minutes. The deaths of all the significant characters are only demonstrations of death though: there is a deeper level of death’s meaning – the investigation Shakespeare makes into death through the mind of Hamlet, and it’s the progress of that investigation that the audience follows by its close identification with the hero.

Hamlet contemplates the physicality of death and its far-reaching complications. In Act 1 he is tortured by grief and misery from the death of his father and the over hasty, incestuous marriage of his mother to Claudius. He contemplates suicide as a solution but restrains himself because of his fear of eternal suffering in the afterlife. In his famous ‘To be or not To be’ soliloquy. He calls the afterlife “the undiscover’d country from whose bourn / No traveller returns” and it is this unchangeable fact – this question that has plagued mankind since its beginning, that holds people captive in a world that is treacherous, miserable, and rotten.

The theme deepens as the action progresses. Hamlet develops an obsession with death. On finding the skull of his father’s jester, Yorick, he contemplates the ultimate physical transition from life to death – even the most alive and vibrant human beings are eventually reduced to a hollow skull. He also ponders on the notion that death is the great leveller and equalizer of human beings. He goes on to describe death as the generator of nature in that human beings are recycled and provide the fertiliser and nutrition that keeps nature working.

Hamlet finally comes to accept death, and indicates that “the readiness is all.” From now on his reflections on death are neither a matter of fear nor of longing. He now fully accepts that without death there cannot be life.

Perhaps the most graphic and horrifying passage on death appears in Measure for Measure. Claudio, condemned to die for fornication, spends the night before his execution in a state of terror as he contemplates it:

Ay, but to die, and go we know not where;

To lie in cold obstruction and to rot;

This sensible warm motion to become

A kneaded clod; and the delighted spirit

To bathe in fiery floods, or to reside

In thrilling region of thick-ribbed ice;

To be imprison’d in the viewless winds,

And blown with restless violence round about

The pendent world; or to be worse than worst

Of those that lawless and incertain thought

Imagine howling: ’tis too horrible!

The weariest and most loathed worldly life

That age, ache, penury and imprisonment

Can lay on nature is a paradise

To what we fear of death.