By Ralph Goldswain

Violence? What violence?

Titus Andronicus was hugely popular when it came out in 1594. Since then, until the twenty-first century, it was largely ignored, probably because its violence was too grossly over the top for the Victorians, who had developed narrow Shakespearean expectations, which this play simply didn’t meet. It’s an early play by an aspiring young playwright, trying his hand at working on a play on his own.

In the process of serving his “apprenticeship” with Thomas Kyd and Christopher Marlowe, two of the finest writers of his time, the young Shakespeare perhaps decided that he would imitate, and even outdo, their huge money-spinning plays, The Revenger’s Tragedy and The Jew of Malta, which are distinguished by their violence.

Titus Andronicus must surely be a parody of those plays, and in aiming for that Shakespeare certainly did go over the top, himself parodying their over-the-top violence. Hardly a moment goes by without someone being murdered or having parts of their body chopped off.

But the play retains all the humour and comedy one would expect of a parody and, indeed, the extreme violence contributes to that effect, simply by its being absurdly overabundant. And this being a play by Shakespeare, it has serious thematic directions –violence, race, revenge, family, war, cannibalism, rape and so much more – even babies! And so, it was a winner – violence for those who went to the theatre especially for that, and thoughtfulness for those who went to the theatre for mental stimulation.

Jude Christian’s all-women production cuts out the violence and turns up the comic tone. Even the method of replacing the physical violence – the torturing and murdering of candles – is funny, and from the first moment, when the cast present themselves as a chorus in a song that signals the disguised violence to come, announcing “torture porn, but more artistic” the audience begins their almost continuous two and a half hour laughing marathon. It is an accomplished performance by a team of talented actors with no weak links.

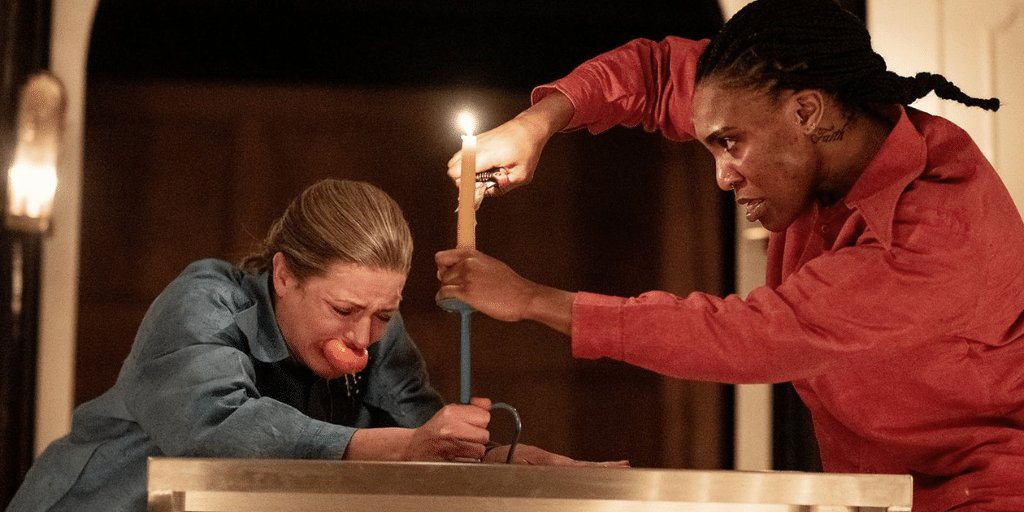

All Sam Wanamaker productions have one thing in common: they do not use stage lighting, but leave the producer to find ways of using candles. In this production, the candles themselves are central to the concept. The missing dimension of bloody violence is provided by the use of candles that represent the victims. Whenever there is a violent action a candle is chopped or broken, smashed with mallets or strangled. When a character dies their flame literally goes out.

Katy Stephens and Kibong Tanji in Titus Andronicus. Photo by Camilla Greenwell

The plot is complicated and quite difficult to follow, particularly as all the actors are dressed in identical silk cultural revolution-style pyjamas in a variety of colours, all women and all with their, mainly dark, hair in a long tail down their back.

They are energetic and speak clearly, and as they work their way through the byzantine plot they hone in on the comic opportunities, in a sense pointing to Shakespeare’s personal sense of humour where, as he so often does, he produces little jewels. At one point Kirsten Foster impersonates a fly, running about the stage buzzing until Marcus kills it.

The action stops as Titus reprimands his brother, reminding him that the fly probably had a mother and father, and saying:

“Poor harmless fly,

That, with his pretty buzzing melody,

Came here to make us merry!

And thou hast kill’d him.”

And when Marcus tells him that he killed the fly because he was:

“a black ill-favor’d fly,

Like to the empress’ Moor”

Titus takes a butcher’s knife and viciously squashes the dead fly. It’s funny and profound and shocking on many levels – and carried out with perfect comic timing by the actors. And in the incident where two of Titus’ sons fall into a hole in the ground – not an intrinsically funny episode – it’s hilariously performed by Beau Holland, playing both sons in burlesque, amid side-splitting audience laughter.

The four songs composed by cabaret duo, Liv Morris and George Heyworth are lively and contemporary, and they brilliantly set and maintain the tone of the performance. The action is supported by a score, composed by Francesca Ter-Berg, in much the way that music does in a film, with sensitive mood-creating strains.

And what does this all add up to? Yes and no, really. To strip the Elizabethan raison d’etre for the audience pouring in to see this play takes quite some swallowing, and no matter how creatively it’s done it leaves the play almost naked. It’s entertaining but as the man in the Elizabethan street might have said, “It’s not what I came here for.”

Have you seen this play yourself? We’d love to hear what you thought of it in the comments section below!

I came up with the same “yes and no” that the reviewer did. This production added comic elements (mostly candle=death jokes). But the grief and revenge-propelling rage are also played to the hilt. As a result, I felt whiplashed, and left the theater feeling like my emotions had been abused.