By Ralph Goldswain

Joel Coen’s 2021 film “The Tragedy of Macbeth” is a tale of two stories – Shakespeare’s and Coen’s – and the result is a remarkable film. If the point of thousands of directors and actors telling the Macbeth story over the course of four centuries is that there are always new things to see in new productions and that directors and actors have the opportunity to reveal them, this film hits the mark.

Shakespeare’s story is about an ambitious young military superstar who, with the help of a perhaps even more ambitious young wife, overreaches himself by killing his king and benefactor with the aim of succeeding him, then, tortured by fear and guilt, descends into a personal hell that ends in his being defeated by those he has sought to marginalise. Coen’s story starts from a completely different place.

In Coen’s story Macbeth and Lady Macbeth are a couple who have already passed retirement age. When we first see Macbeth he is completing another – surely his last – military mission, putting down a serious rebellion, and although regarded by others as a hero, to him it’s all part of his day job, something he does without an adrenaline surge these days. Lady Macbeth is much more passive than we usually see her: she is the weary wife in a long marriage, supporting and encouraging her husband in a project he wants to engage in rather than the sharp, thrusting, highly ambitious woman we think we know, who pushes her husband hard with every trick in the book, harder and harder as he wavers, unremittingly merciless, until her mind finally breaks. In Coen’s story she is a prop for her husband rather than a goad.

Coen’s interpretation is expressed by a team of three, Joel Coen himself, Denzel Washington and Frances McDormand, working together to tell that story.

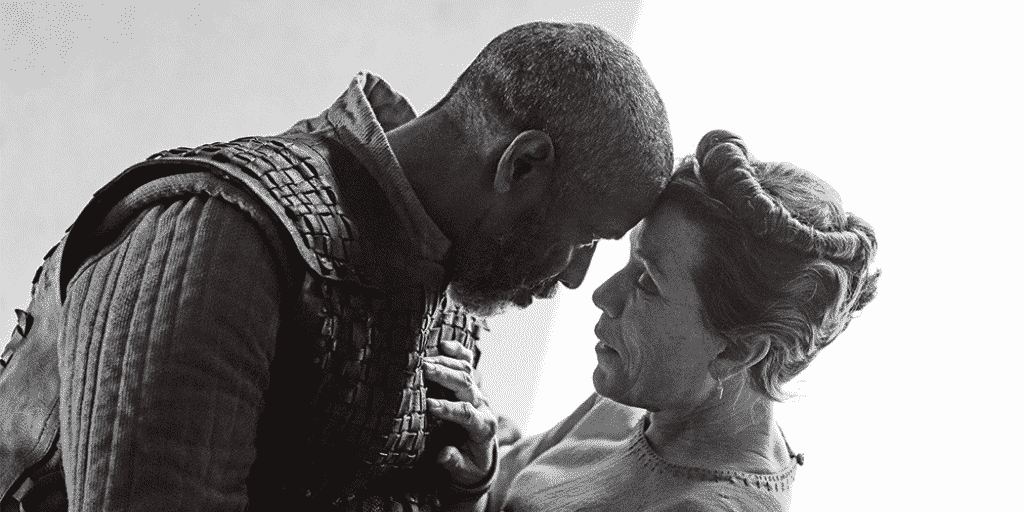

Francis McDermot and Denzil Washington star in “The Tragedy of Macbeth”

Washington is a somewhat tired Macbeth, playing down the passion in Shakespeare’s language, which is edited by Coen to allow that. He presents a man who, rather than looking towards a future as a dazzling young king, all set for a lifetime of wealth and power, is looking at his last chance to achieve that golden round – the crown – as though he deserves it after all he has done. As though it’s his turn. He plays it as a man who owes it to himself after a long career of service. He does it without passion, almost with resignation.

Francis McDormand is not recognised as one of America’s greatest film actors for nothing. Because of the screen rather than the stage mode of this production the camera is one of the keys to our understanding of her interpretation. Her close-up facial expressions and body language are a major aspect of this drama. We see sympathy for her husband, affection, disappointment, shock, disillusion, all on her face, on a track that accompanies the text. By using that combination of physical activity and his editing of the text Coen is able to fit Lady Macbeth’s character into his interpretation. In the banquet scene, where Lady Macbeth gets impatient and cross with Macbeth in the text, it is underplayed in the film and we have sympathy and support for her husband instead. And possibly the most haunting and memorable image of the film is that of Lady Macbeth, just before her suicide, standing alone on the battlements watching as Birnam Wood advances on the castle. It is an image of sheer disappointment, the very picture of terminal sadness. In this version she dies, not of madness caused by guilt, but of mammoth disappointment in the way their final project has turned out.

Denzel Washington handles the dialogue better than some of the “great” actors of the past in that he understands what Shakespeare is doing with iambic pentameter and exploits its flexibility to suit his interpretation of the role. In meeting and working with Christopher Marlowe, Shakespeare picked up the technique of writing poetic dialogue that used the rhythm of natural speech, and developed it to the point where an actor could say the lines in a way that communicated with audiences as effectively as vernacular language while at the same time spinning its poetic magic in the back of the mind. Washington masters that and it contributes to Coen’s vision of a less passionate assassin. The “If it were done when tis done” soliloquy for example, is full of yearning, straining, brimming with youthful physical vigour but, without changing a word, Washington dampens all that and emphasises the mature, philosophical aspect of the soliloquy with his calm, reflective world-weary delivery.

It seems clear from more usual interpretations, and also from Shakespeare’s text, that Macbeth holds the sympathy of the audience until, in the middle of the play, his murderers kill a child onstage – an outrageous, shocking moment. It is then that we realise that Shakespeare has been taking us slowly away from our identification with him. With outside reports of his barbaric behaviour and language like “butcher,” “tyrant,” the references to birds of prey etc. we begin to see him through the eyes of his victims. After the murder of the child we are on the side of his opponents as they hunt him down and we applaud them as they corner and behead him.

Coen’s story is different. We stay with Macbeth throughout. There are enough glimpses into his soul in Shakespeare’s text, to allow us to stay there, like the “tomorrow and tomorrow and tomorrow” soliloquy. Coen skims over most of the references to Macbeth as a bloodthirsty tyrant, spares the blood and language about blood that characterises the text, and usually drenches stages and screens, and he ignores most of the signs of the Macbeths’ disintegrating marriage. In the film we follow Macbeth in sympathy throughout and the result is that we accompany him, rather than his opponents, in his downfall. In that way Coen turns the play into something of an Aristotelian tragedy, where a flaw in the tragic hero causes him to make a misjudgement that results in his downfall, which the audience follows, experiencing pity and terror, and finally, catharsis, as the hero’s life ends with partial insight into the fault that has brought him to that point.

In the Shakespeare text we have something not as purely Aristotelian. We have, instead, an exciting murder thriller with a manhunt and a final showdown between the good guys and the bad guy, who is now Macbeth, in which the bad guy pays for his crime and, instead of the Aristotelian catharsis, we have the satisfaction of seeing the good triumph over the bad.

Those are two very different visions for the tragedy of Macbeth.

The film’s stark black and white is reminiscent of Lawrence Olivier’s “Hamlet,” with the action taking place in a bleak castle. Here, though, the castle’s interior is more like that of a large house built by a progressive modern architect, with plastered walls and tiled floors. Characters emerge as though materialising out of a white mist and disappear back. Ravens fly everywhere, including inside the castle rooms. The witches transform themselves into ravens and the ghost that only Macbeth can see turns out to be a raven trapped behind closed windows, frantically trying to escape.

One of the most enjoyable things about this film is the array of fine, and well known actors playing the minor characters, from Brendon Gleeson as Duncan to Miles Anderson as Lennox. A special word must be said for Coen’s presentation of Ross, played by Alex Hassell. Ross is a mysterious enough figure in the Shakespeare text and Coen turns that up and offers an interpretation of him as an unearthly character, fitting no type and operating on both sides of the political divide. He appears at different times, sometimes unexpectedly, and that, together with his being more outside the action, like an observer, but sometimes manipulating the action, than a traditional character acting within the story, lends a postmodern feel to the film.

Apart from Washington and McDormand, the standout performance is by Kathryn Hunter as all three witches. She uses physical contortions and distinctly different voices. She twists her body into a variety of shapes, using her limbs to create the kind of images that appear in horror films as monsters. The combination of those exercises and creative camera work make for the most frightening and memorable of witches.

Joel Coen’s “The Tragedy of Macbeth” will join the landmarks of Shakespeare films and will become important in the discourse around the performing of Shakespeare. And how wonderful it is that along with such Shakespeare film performers as Orson Welles, Laurence Olivier and John Gielgud, Denzel Washington’s and Francis McDormand’s performances will be preserved for all time.

Have you seen this film yourself? We’d love to hear what you thought of it in the comments section below!

Although director Joel Coen makes some inventive choices in the introductory scenes, he asks the actors for performances that are so flat in the first act and a half as to make the story incomprehensible. Yes, the original material starts at a low energy level and finishes with one of the great swordfights in the history of showbiz, but this is extreme.

However, gathering his actorly powers as he ramps up to the murder of Duncan, Washington at last achieves epic (anti-)heroic energy. From then on, we can enjoy one story-telling innovation after another. The fight with Young Siward is as character-defining as it has ever been, and becomes a magnificent prologue to the final showdown with Macduff.

One more thing: I happen to believe that Mr. W.S. would approve of how Coen uses Ross to tie up a few loose ends.