By Ralph Goldswain

With a cast of only eight actors, bringing this great play, which has some of Shakespeare’s major roles and scores of minor characters, with battle-ground and civil crowd scenes, to the stage is a sleight of hand, which Diane Page effectively manages.

That’s largely due to the flexibility and fine acting skills of the supporting cast. Cash Holland and Amie Frances as Portia and the innocent bystander mistaken for Cinna the poet and having to absorb the mob’s anger, respectively, deserve a special mention, with Amie Frances, particularly, putting everything into being beaten to death. The prize though, goes to Omar Bynon as the cobbler who starts the ball rolling, bringing the audience into the action from the word go, prompting them to shout “Pompey is pants” as he conducts them. Audiences love that, and here, too, being given the opportunity to cheer Marc Antony on when he addresses the crowd. Ms Page blurs the lines between stage and real-life by extensive use of the audience in that way, the audience yelling out its fickle political allegiances, and it works beautifully.

It is the power tug-of-war – tyranny, freedom, war and peace – as it manifests four centuries after the play was first performed that interests Diane Page. Her preoccupation with any classic is what that story means to us now, she tells us. “I wanted to repurpose Julius Caesar to challenge what power looks like now, especially for women,” she wrote. So the question is, how successful has she been?

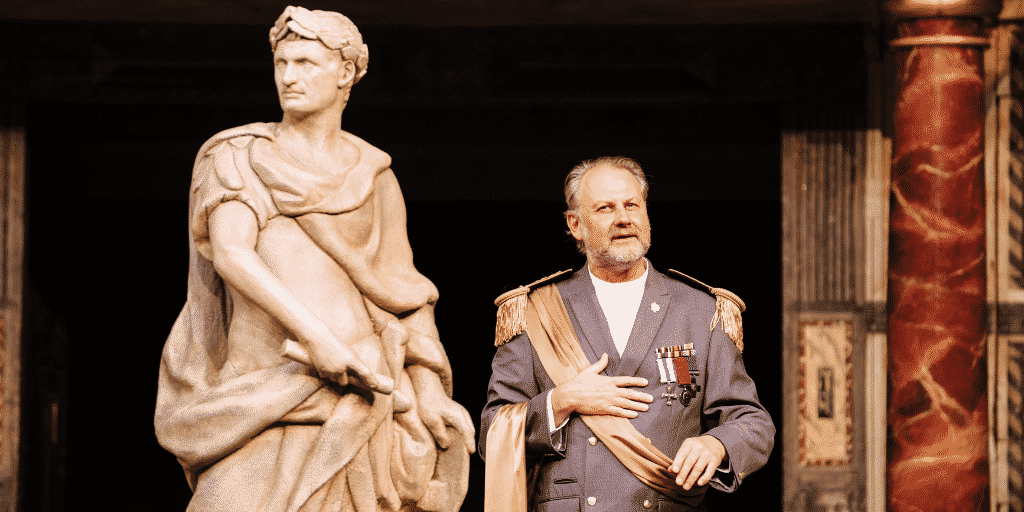

Dickon Tyrell’s well-rounded Caesar exhibits Trumpian characteristics, both in public, in military uniform, and at home in his dressing gown, with some very fine acting, able to bring out Caesar’s unwillingness to heed advice, his vanity and the chink in his armour, a fatal susceptibility to flattery, in spite of his having to rush through it in the context of a speedy pace for that section of the play.

Picture Dickon Tyrell as Julius Caesar Copyright © Helen Murray

Samuel Oatley’s interpretation of Marc Antony is interesting and refreshing. Behind the serious, power-grabbing politician is a fun-loving laid-back human being, always threatening to inject humour even into his great “Friends, Romans, countryman” oration. And he performs that speech, with all its cynicism and manipulative skill, to perfection.

There are also some nice touches that meet Ms Page’s intention, such as the Trumpian Caesar’s ‘cancelling’ by the removal of his statue, like the felling of that of Sadam Hussein and the removal and dumping of Edward Colston’s in Bristol harbour.

It is in the later, post-interval, section, where the relationship between Cassius and Brutus is developed, that Ms Page’s interest really lies, though. She has invested heavily in reinventing the characters as women – Charlotte Bate as a lean and hungry-looking Cassius and a more serious better-fed Brutus, played by Anna Crichlow, and it’s there that things begin to fall apart.

By changing the gender of the two characters Ms Page has the obligation to think her decision through, and convince us, and here, possibly lies a problem. These are two very masculine characters, speaking the macho language of two men more involved in violent acts than in anything else. Putting it in the mouths of women somehow doesn’t ring true. Mixed into that are some unsatisfactory loose ends, such as Brutus being in a same sex marriage. Interesting, nothing wrong with that, but where does it go in this production? And there are suggestions of a sexual attraction between the two characters. Nothing wrong with that, but where does it go as regards the meaning of the play? That aspect is introduced but not explored.

‘Love’ is a major theme in the play. In Shakespeare’s text it’s essentially about the Roman concept of love, which is about friendship, respect by one man for another, and patriotism – love of country – so when Brutus says he loved Caesar but he loved Rome more it’s about all those things, and when he addresses the crowd as ‘lovers’ he’s appealing to their patriotism. And Marc Antony also means that as he proclaims his love for his assassinated friend. However, when Cassius and Brutus have their big row Charlotte Bate wails “You love me not,” in a very feminine way, she’s interpreting the line as a complaint by a woman abandoned by a lover, thereby losing some of the main themes, or at least, warping them, and substituting a Page-invented theme that goes nowhere.

In Shakespeare’s theatre all the female roles were played by boys and young men. Audiences were used to that and with the boys in appropriate costumes the suspension of disbelief came quite naturally. In many present day productions women play male roles, as men, in appropriate costumes, and the same applies. However, changing the gender of a Shakespeare character can raise questions that have nothing to do with the meaning of the play. And that’s what’s wrong with this production – too many untied-up loose ends, particularly in the second part of the play, which is often a somewhat shrill, over-emotional shouting rather than Shakespeare’s punch-by-punch, carefully sculpted, argument between an angry man and a better composed, also male, adversary. While the acting of these two actors is competent, to play these two major Shakespeare males, using the carefully crafted masculine language, is a big ask. There’s a frequent mismatch between the masculine rhetoric and the female physical gestures and mannerisms.

The questions of power and authority are clear and evident in Shakespeare’s text. They are already thoroughly relevant to our lives today. There is some valuable highlighting of issues of our time in this production, though, such as the difficulty women have in gaining access to power. Also, the way the two women, as Cassius and Brutus, go beyond the pure power grabbing we see in the three men – Julius Caesar, Octavius and Marc Antony – to more of a philosophical concern with that naked power drive as a detriment to civil life. Ms Page has the right to explore those things, and to stretch Shakespeare’s text. It’s the done thing in Shakespeare performances these days. But she dilutes the action and plays loose with the rhetoric, twisting it to her purposes. It doesn’t quite work, but three cheers for her for trying.

Have you seen this play yourself? We’d love to hear what you thought of it in the comments section below!

Great review, agree. The play was a mess – the re-pronouning was confusing. And sorry to say but the acting was largely uncomfortable and a bit forced, not natural or believeable.

Absolutely agree with the comment above. Weak acting on the whole and the great Marc Antony oration one of the dullest addresses outside Slough! Good to watch how much some school-boys in the pit enjoyed being involved in the action though!

Julius Caesar – Globe Theatre Cast – Magdalen College School – 23.7.22

Marc Antony’s speech – Act III, Scene II – was a joy to behold! Samuel Oatley delivered it convincingly, with authority, and, of course, the writing is brilliant! Because that speech is so brilliantly written, it was not possible for the Director to ruin it in the same way that she ruined so much of the rest of the play.

But for my wife – who enjoyed the play – I would have left at the interval, and would have missed the best bit. It restored the role of Antony, briefly, to its rightful interpretation. I knew my perceptions were in trouble at the very beginning, when Marc Antony made his entrance as an open shirted, beer swilling yobbo. Things went further downhill, when I realised that Cassius and Brutus were being played by women. Cassius’ shrill, hysterical ravings were a reality away from the conniving, manipulative, masculine rivalry that, to me, seems necessary for verisimilitude. And, is it me? Or is anyone else totally fed up with the continual ‘Larry the Lamb’ tremulous voices that some actors (or directors?) seem to think is essential in order to convey emotion in Shakespearean productions? To my knowledge, Richard Burton didn’t ‘baa!’ when playing Shakespeare? The words ‘overacted’ and ‘ham’ are the ones that spring to mind in context with what I unfortunately witnessed yesterday.

I am not a theatre critic. I’m not an expert. I have never written my comments on any sort of dramatic production, and probably never will again. However, I thought yesterday’s performance was so wrong that, when presented with the opportunity, I felt obliged to write down what I think. I go to the theatre to be entertained. If there is a better reason for going, please explain it to me. I was not entertained by this interpretation of Julius Caesar. Quite simply, it was the worst theatrical production I have ever seen.

Well, Bill, you and I are in complete agreement. Thank you for your comments. We both identified the strengths of this performance, and I said the same as you have indicated about the feminisation of the Brutus/Cassius roles. You say you are not a critic. Perhaps you should rethink that!

Hello Ed – thank you very much for the feedback. It’s good to know that others share your views. All the best, Bill.

Absolute travesty. Yelling, no understanding of what they were saying, the actors had zero conviction. But noone stuck the knife in as deep as the director. Et tu Pageus

This review is boiling over with barely-masked misogyny. “Putting [the text] in the mouths of women somehow doesn’t ring true”? Why can’t you believe a woman could be Brutus? Or Cassius? Because their voices are too high? Because – because – because? You say ‘somehow’ – you’re not even sure why.

“Shakespeare’s punch-by-punch, carefully sculpted, argument between an angry man and a better composed, also male, adversary” Do you mean this petty squabble?

CASSIUS When Caesar lived, he durst not thus have moved me.

BRUTUS Peace, peace! you durst not so have tempted him.

CASSIUS I durst not!

BRUTUS No.

CASSIUS What, durst not tempt him!

BRUTUS For your life you durst not!

The words are exactly the same. Why is it suddenly ‘over-emotional’ when performed by women? Why is it ‘shrill’? Would you consider all the female parts ‘shrill’ in Shakespeare’s day when performed by teenage boys?

Same here: “There’s a frequent mismatch between the masculine rhetoric and the female physical gestures and mannerisms.” What makes these words masculine? Because men have said them? Ariel is textually a man, can women no longer play him? Are his words masculine inherently? Are you about to complain that women playing women in Shakespeare don’t have the proper mannerisms of teenage boys?

“However, when Cassius and Brutus have their big row Charlotte Bate wails “You love me not,” in a very feminine way, she’s interpreting the line as a complaint by a woman abandoned by a lover” Why is it bad that she wails ‘in a very feminine way’? She is a woman. And I disagree – she’s not abandoned by a lover, she’s abandoned by a friend (I’ve never seen a Caesar with *less* tension between Cassius and Brutus). Why are the emotions and expressions of a masculine Cassius so much more tolerable than Bate’s?

“Mixed into that are some unsatisfactory loose ends, such as Brutus being in a same sex marriage. Interesting, nothing wrong with that, but where does it go in this production?” Why does it need to go anywhere? A ‘straight’ Brutus serves no more narrative purpose than a queer one. We don’t question why Portia is included at all, why a male Brutus is married to a woman: why should we wonder about a female Brutus and a female Portia? And with Cassius and Casca, while the tail end is dropped (why not have him die like the NTL Caesar?), the flirtation adds bite to Cassius’ monologue in the storm, rage to her first stab at Caesar, and a subtle addition to the theme of her affection-seeking that carries through this particular production. Well, that’s just an opinion.

Every other review of this production is full of subtle (and not-so-subtle) prejudice and I’m so sad reviews like this one have masked over any real criticism of the production. Time moves on. Julius Caesar is unscathed. Your (and my) beloved text has withstood 400 years of interpretation. I’m not quote-unquote cancelling this review. You’re still allowed to not like it. God knows I didn’t love it. But perhaps you should interrogate why, exactly, you can’t let a woman take up space in Shakespeare.