“A foregone conclusion” is one of the many terms lifted from Shakespeare that regularly slips into our communication with others. It’s not an idiom like “all that glisters is not gold” – it is just a term. It’s deeply embedded in the English language, as there is no better way of talking about an inevitable outcome, or a decision formed in advance of a proper exploration of the alternatives.

One may say, for example, “It’s a foregone conclusion that she will pass her exam as her nose has been buried in her books for a week,” or “the polls are so strong for that candidate that her election is a foregone conclusion.”

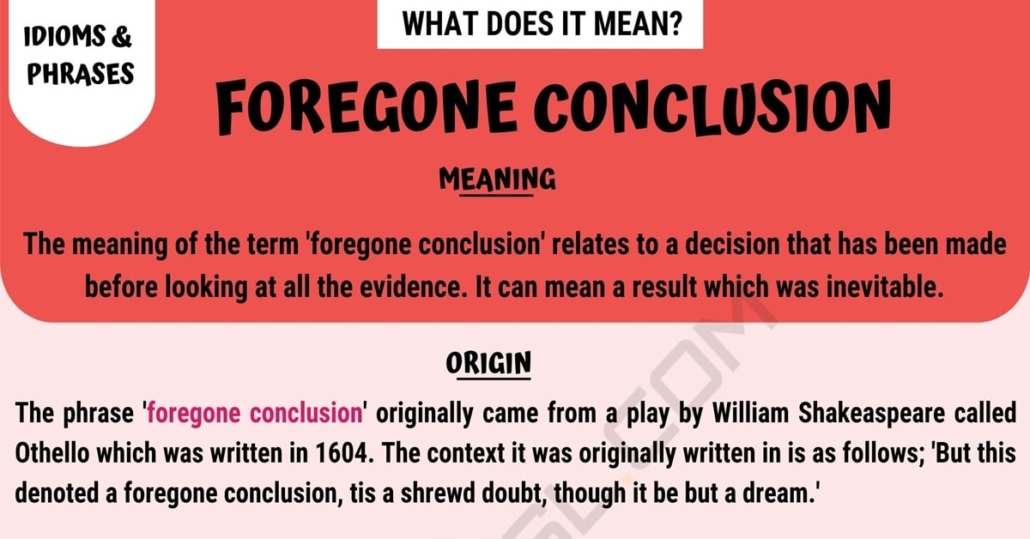

What is a foregone conclusion?

Where does ‘foregone conclusion’ come from?

“A foregone conclusion” comes from Shakespeare’s play Othello (Act 3, Scene3).

The general, Othello, has come under the spell of the sociopath, Iago, an officer in his regiment. Iago is bent on destroying him and his plan, knowing that Othello is capable of extreme emotions, is to suggest that his wife, Desdemona, is having an affair with his second in command, Michael Cassio. He tells Othello that Cassio has been talking in his sleep about making love to Desdemona. Othello soon says it’s a foregone conclusion that Desdemona has committed adultery with him.

The meaning here is that this speculation suggests proof of her adultery, and Othello’s mind quickly follows that direction:

Othello: O monstrous, monstrous!

Iago Nay, this was but his dream.

Othello: But this denoted a foregone conclusion.

Iago:‘Tis a shrewd doubt, though it be but a dream,

And this may help to thicken other proofs,

That do demonstrate thinly.

When Othello talks about a foregone conclusion, the word “conclusion” has a double meaning – it refers to the climax of lovemaking, the actual sex act. There is no suggestion of that in the modern use of the term, however.

“A foregone conclusion” joins hundreds of other everyday terms that we don’t know come from Shakespeare until someone tells us. Some others are “break the ice,” “fair play,” “catch a cold,” “fancy-free,” “heart of gold,” and so on – many many more.

Those everyday terms are not idioms like “dead as a doornail,” or “neither a borrower nor a lender be,” or “all is not gold that glitters.” They are just phrases that Shakespeare uses throughout his texts that later writers and orators have liked and found perfect for expressing the thing they want to say – always compressed, using a minimum of words, but perfect – and picked up and used in everyday conversations.

On that basis, just about every one of Shakespeare’s phrases should be included in that category, but that’s not so. There are plenty of Shakespeare phrases that didn’t catch on as everyday phrases, like “well at peace,” “he has borne all things well,” and “treason has done his worst”.

It’s a mystery why some of the Bard’s phrases have stood the test of time while others have fallen by the wayside. But it’s certainly true that if one opens a Shakespeare text at random one will very soon come across something that has become an everyday phrase in the modern language, and as one reads there will be more and more, all the way to the end.

Because generations have found things in Shakespeare’s texts relevant to their age over the past four hundred years and included phrases from his plays in their speech as the English language has developed, and continues to develop, it is a foregone conclusion we can expect more of Shakespeare’s phrases to be picked up for everyday use as the centuries go by, and as yet undreamt-of human circumstances emerge.

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!