Robert Pattinson. Shakespeare. And Timothée Chalamet’s hair. Clearly, Netflix knows exactly what I’m into. The King, a feature-length film based on the Henriad (Shakespeare’s Henry IV Part 1, Henry IV Part 2, and Henry V), was released in November 2019, much to the glee of Shakespeare geeks everywhere. The film blends elements of history, Shakespeare, and completely new material.

The story might sound familiar: Prince Hal, heir to the English throne, loves turning up on the outskirts of town with his friends, including a jolly dude named Falstaff. When Hal’s father dies, he is compelled to change his behavior, learn how to be a real king, and lead a war against France. That story is a bit different from history – turns out, Hal wasn’t that big of a partier, and Falstaff didn’t exist in real life at all.

However, though they share that same central plot, The King pulls away from the Henriad in ways that alter the entire message of the story. And those changes are exactly what I want to get into. This isn’t really a film review, per se. I had some qualms with the film, from pacing to consistency – but I am more interested in how it interrogates Shakespeare’s plays. What does it change, what effect do those changes have, and how does it change our view of Shakespeare’s plays? And, most importantly, why does Edward Cullen have such a weird French accent?

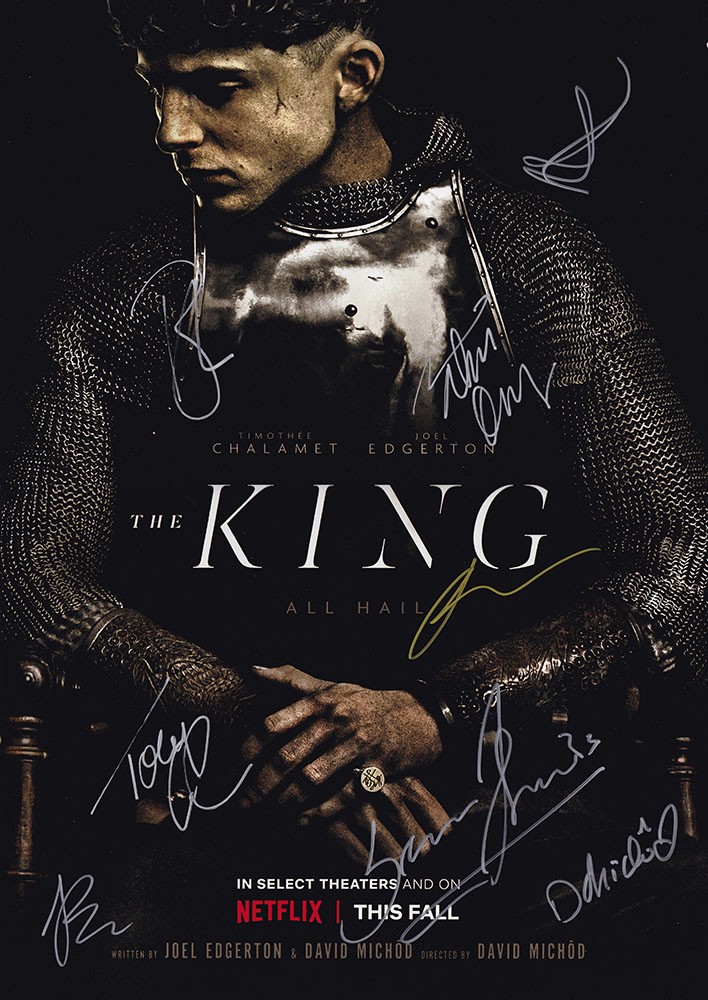

The King, Netflix promo poster

So… Shakespeare’s Falstaff is a big buffoon. He’s a gambler, a thief (albeit not a very good one), a joker, and a great lover of food and drink. Though we’re told he’s a knight, he seems to exist in a world outside of monarchy, politics, or war. He behaves in opposition to the type of king that Hal is expected to become – one that is measured, wise, and strategic. Falstaff was beloved for his humor and jollity; it’s said that the Queen herself asked for another play with Falstaff, which was why The Merry Wives of Windsor was written.

Though Falstaff is a fictional character, it is supposed that he was originally based on a real-life figure: Sir John Oldcastle. That, says The King actor, writer, and producer Joel Edgerton (who plays Falstaff in the movie), was how they decided to reshape Falstaff:

“We were looking at the real-life of a man called John Oldcastle, who a lot of people say that [Falstaff] was based on (…) who had fought a war, had been a general. (…) Imagine it’s the war-weary version of Falstaff, rather than the large jester.”[1]

That alteration is apparent in the character they create for this film. Though they make an effort to hold onto parts of Shakespeare’s version of Falstaff (he drinks, gets in debt at the local tavern, and is referred to as a poor “thief”), this film changes Falstaff from a jester to a sage. From a man who ends his life spurned by the new king, to a man who sacrifices his life on the battlefield. So, the question is: what exactly does changing Falstaff’s character do for the message of the film? And what does that alteration do for the story of Henry V?

From the beginning of the film, we see that Falstaff acts more as Hal’s caretaker than his compatriot. Yes, he parties with him, but he also helps him transition into his role as the leader of England. Hal refuses to go see his father, the King, whom he hates, in the first few minutes of the film. Falstaff, however, convinces him to go. Then, after Hal defeats Hotspur in single combat, Falstaff is the one who empathizes with him over the horrors of killing in battle: “Nothing,” he says, “stains the soul more indelibly than killing. Never have I felt so vile than standing victorious on a battlefield.” Does that sound like the same Falstaff who, in Shakespeare’s play, plays dead to avoid the battle, then pretends to stab Hotspur to get credit? Yeah, didn’t think so.

Falstaff as portrayed by Joel Edgerton. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

While Shakespeare’s Prince Hal needs to turn away from Falstaff to become king, The King’s Hal sees keeping Falstaff close to his side as integral to his leadership. In this film, Falstaff’s advice is far more important to Hal than the political leaders who are supposed to advise him. By bringing Falstaff with him, Hal eliminates the strict boundary between his debauched past and his royal present. But, by the end of the film, there seems to be a question as to whether Hal was the right ruler for the kingdom at all. Rather than ending on a successful and comic union between Henry and Catherine, between England and France, The King ends with Hal facing the fact that his war – and his crown – were built on lies.

In the play, the scene where Hal meets his new fiancée, Catherine, is a humorous scene involving linguistic confusion. But, in the film, it is a scene of perfect understanding and chilling truths: Catherine ruins Hal’s perception of himself as a kingly figure by informing him that he was never victim to an assassination plot from the French. The reason he was given to start the war was, in fact, a lie. Instead, she tells him, “A unity that is forged under false pretenses will never be a unity that prevails,” and then throws a serious punch: “All monarchy is illegitimate.” This is one of the biggest changes from plays to the film – we end Henry V believing that both Henry and the war are honorable. This film rips our certainty away and makes us review everything we thought we knew about the story with a critical eye.

So, if all monarchy is illegitimate, who does The King suggest fill that role? Well, anybody with uncompromising morals. And, in this story, that’s Falstaff. The film takes Shakespeare’s positioning of Falstaff as the everyman, the lover of life, and molds him into a policymaker, an instigator for effectual change. When Hal starts having to make serious decisions about how to run the war against France, it is Falstaff that he goes to for advice. When introducing him as general to the rest of the commanders in the army, Hal proclaims, “I have tasked Sir John to join this campaign for one vital reason: he respects war as only a man who has seen its most monstrous form can. He lusts after it not.” Hal, too, is not eager for conflict; he avoids war with France as long as possible, asks to fight in his armies’ stead at both the battles of Shrewsbury and Agincourt, and seeks out military strategies that will spare as many men as possible. We know his father and brother are hungry for war, so we can assume that his respect for mercy and peace came not from royal education, but from his friend Falstaff over a barrel of ale in an Eastcheap inn.

The film isn’t pulling this message out of thin air. This insistence on the everyday Englishman being someone of importance has its roots in the Henriad. In Henry V, Hal disguises himself as a commoner so he can speak to his soldiers about their opinions of him and of the war. Then, in his famous St. Crispin’s Day speech before the Battle of Agincourt (“Once more unto the breach, dear friends!”), he stresses that “he today that sheds his blood with me shall be my brother.” The version of that speech in The King strikes a similar chord: Hal cries, “You are England!”.

Timothée Chalamet as King Henry V in The King. Photo courtesy of Netflix.

Unfortunately, toward the end of the film, Hal steers away from the advice of his noble general Falstaff. Before the battle, Hal orders Falstaff to kill all the prisoners. Falstaff says that he won’t, and that Hal would have to do that himself if he wanted – but he says that he knows that Hal won’t because he’s “not that man.” If only that were true. That is some of the last advice Falstaff is able to give the young king because he soon dies a grisly death on the battlefield. But, at the end of the battle, in what should be a moment of pure triumph and glory, a true display of a king in his prime, Hal goes against everything both he and Falstaff claimed to stand for. A man approaches Hal with a warning that the prisoners could all turn against them. Hal has just seen his friend’s body in the mud – there is no doubt that the thought of prisoners would remind him of Falstaff’s advice. But, without missing a beat, Hal orders: “Kill them all.”

So, that brings us back to his conversation with Catherine, in which Hal realizes that the war he waged on France was under false pretenses, and that he unwittingly sacrificed his moral principles merely for political gain – the kind of maneuver he had always claimed to despise. It is then that we begin to realize alongside Hal that, maybe, winning this war does not make him the leader he is presented as at the end of Shakespeare’s Henry V.

The Henriad shows us the journey of the young boy to the fully realized king: a bildungsroman of nobility, a handbook on true leadership. But The King stops short of that, instead suggesting that real leadership requires an unflinching devotion to moral principles, rather than needing to adopt a severe approach, as the plays suggest. But, for all its cynicism, maybe, just maybe, we get a hint of the kind of leadership The King yearns for in its Falstaff. At the end of the Battle of Agincourt, as the rest of the English army celebrates, the camera pushes forward, centering on Falstaff’s outstretched, peaceful form lying on the battlefield – and a chorus of men in the background cry, “Long live the King!”.

Have you watched The King on Netflix? If so, what do you think? Let us know in the comment below!

See reviews of Romeo and Juliet movies >>

See reviews of Macbeth movies >>

See Shakespeare in Love movie review >>

See all Shakespeare movie reviews >>

[1] Interview with Screen Rant about The King, Netflix: https://screenrant.com/king-movie-joel-edgerton-interview/

Enjoyed the piece. Thank you.