Whether you’re a Shakespeare nerd, a 90s cinephile, or you just had to watch them in school, you’ve probably been exposed to Kenneth Branagh’s Shakespeare film adaptations somehow. And, if you’re lucky, one of them was his 1993 Much Ado About Nothing.

The movie’s star-studded cast should turn your head alone: a young Denzel Washington plays Don Juan, Keanu Reeves has a surly turn as Don John, Michael Keaton is an oddly Jack Sparrow-like Dogberry, the illustrious Emma Thompson is the devilishly witty Beatrice, and Branagh himself plays her stubborn love interest, Benedick.

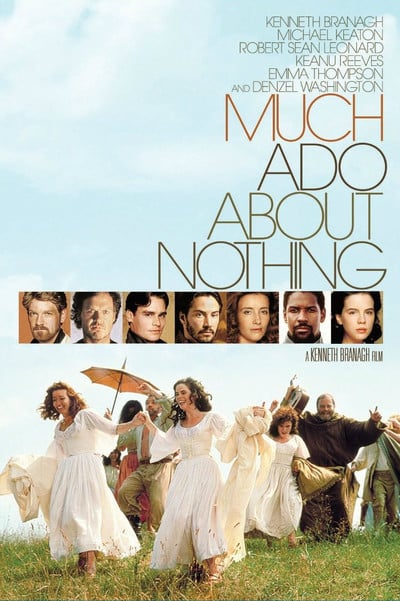

The poster for Branagh’s 1993 Much Ado About Nothing.

Loaded cast lists like these are common of Branagh’s Shakespeare adaptations – after all, what better way to get people interested in centuries-old text than casting some of their favorite actors? For example, his 1996 Hamlet stars Kate Winslet as Ophelia, his Henry V has Robin Williams as the Fool (and slips in a very young Christian Bale!), and his 2019 Shakespeare biopic All Is True stars noteworthy actors like Judi Dench and Ian McKellen (better known as Gandalf or Magneto). In all the films, Branagh himself plays the lead male role.

But rarely is a cast so cohesive and dynamite in their performance than in his 1993 Much Ado About Nothing. First of all, this was the 90s, so all of these actors were in their prime. Branagh and Thompson, in particular, have a mature, but still heart-achingly youthful and giddy match in Beatrice and Benedick.

If you’re not familiar with the story of Much Ado, let’s fill you in really quick. Essentially, two young people, Hero (played by Kate Beckinsale) and Claudio (Robert Sean Leonard) fall in love and intend to marry. Hero’s cousin, Beatrice, is a little more resistant to love; So is Claudio’s friend, Benedick. Both Beatrice and Benedick claim they will not marry, and, through a series of verbal spars, that they do not like each other. Of course, neither of those statements turns out to be true.

Emma Thompson and Kenneth Branagh play enemies-turned-lovers Beatrice and Benedick.

There’s a great deal of chaos when the self-proclaimed villain, Don John, stages a setup to trick Claudio into thinking that Hero has cheated on him, he leaves her at the altar, she has to pretend to be dead until her innocence is revealed, and somewhere in there Beatrice and Benedick finally admit that they love each other. Everyone gets married at the end, and there’s joy and frivolity all around.

It is this frivolity that separates the 1993 Much Ado About Nothing from many of its cinematic Shakespearean predecessors. Adaptations by greats like Laurence Olivier used to be all the rage — films whose goals were to be reverent to the Bard, to focus on the vastness of language and the impact of Shakespeare on English literature.

But Branagh’s film finds a new way of paying respect to Shakespeare. Rather than taking himself and the text too seriously, Branagh creates what Shakespeare intended: a comedy that guffaws at reverence and is pure fun. Branagh’s film is immediate. Though the setting is nebulously period, it feels like a film made in the here and now; it’s not a movie that seeks to stay in Shakespeare’s shadow, but rather to use his text to create a great work of art in itself. Branagh doesn’t tremble before Shakespeare, he embraces him and his playfulness.

In fact, somehow Branagh’s film seems even to blur the boundaries of cinema and theater. Most actors in contemporary Shakespearean films tend to act much smaller than they would on stage – mumbling monumental phrases like “to be or not to be” so that they sound more “natural,” more fitting for a close-up. Branagh ignores all of that. Instead, every emotion is displayed full-out: Hero’s rejection at the altar is portrayed with screams and cries, Don Jon’s wickedness is practically nuance-less, and Beatrice and Benedick’s sudden switch from mock hatred to love is a whiplash of heightened emotion.

Benedick (Branagh) shouts with joy when he realizes he’s in love with Beatrice.

Even the film techniques seem to lend themselves more to the “unnatural” theatre. When Thompson’s Beatrice and Branagh’s Benedick finally realize independently that they love each other, even though they are not in the same physical place their images are superimposed on each other so that they can be on-screen at the same time. We see Thompson laughing with glee on a swing and Branagh dancing around a fountain, both independently ecstatic. We might see this kind of split-screen on stage, or in a much older movie, but Branagh brings Shakespeare’s theatricality into his 1993 Much Ado About Nothing.

Even the physical scope of the movie screams largess. The setting is at once small and massive; though we are usually confined to the hallways, gardens, and etc. that one might see on a stage, we also see shots of the magnificent Italian countryside these people live on – a countryside that a Shakespearean audience would have been called upon to imagine surrounding the actors onstage.

And, at the end of the film, we see a small wedding dance begin between the characters we know, the way a dance may begin onstage. But, with an arial view, the camera begins pulling back farther and farther until we see that the entire town is dancing together. Again, one person would have had to represent ten onstage to get an idea of the town all dancing together, but Branagh seizes on the opportunities afforded to him by film and creates an expansion of the written text.

Branagh uses the capabilities of film not as an alternative to the stage, but rather to fully realize its strengths. In many ways, in his 1993 Much Ado About Nothing Branagh comes closer to Shakespeare’s vision of the story than even Shakespeare was capable of creating at the time – and he does it all with a laugh.

What do you think about Branagh’s 1993 Much Ado About Nothing? Is it your favorite film version of the play? Let us know in the comments below!

See reviews of Romeo and Juliet movies >>

See reviews of Macbeth movies >>

See Shakespeare in Love movie review >>

See all Shakespeare movie reviews >>

Leave a Reply

Want to join the discussion?Feel free to contribute!