John Donne 1572-1631

John Donne must be one of the most interesting writers who ever lived, both as a poet and a man. His life was a colourful adventure and his poems are significant feats of language.

A Jacobean writer, more or less a contemporary of Shakespeare, Fletcher and Webster, but very distant from those theatre writers, both regarding his social class and his literary work, he is now regarded as the pre-eminent poet of a type of poetry that we refer to as the ‘Metaphysical Poets.’

Donne was a man of significant talent and ability. He was born into a Roman Catholic family at a time when being a Catholic was illegal and this was a disadvantage to him during the first part of his life. At the age of eleven he was entered at Hart Hall (later to become Hertford College) Oxford, where he spent three years, and was then admitted to the University of Cambridge where he studied for a further three years. Neither of the colleges awarded him a degree because he was a Catholic.

In 1591 he began studying law and qualified as a lawyer. By this time he was well known around London as Jack Donne, man about town, party-goer and womaniser. Keen to see the world he set out and crossed Europe and 1596 found him at Cadiz, fighting the Spanish with the Earl of Essex and Sir Walter Raleigh.

He lived in Italy and Spain for a few years and on his return to England, aged 25, he was appointed secretary to Sir Thomas Egerton, the Lord Keeper of the Great Seal. He moved into Egerton’s London house and before long, fell in love with his niece, Anne More. Her father and uncle opposed the marriage but the couple went ahead, eloped and were married. Donne was captured and imprisoned. In a letter to Anne he famously signed off with ‘John Donne, Anne Donne, Undone.’

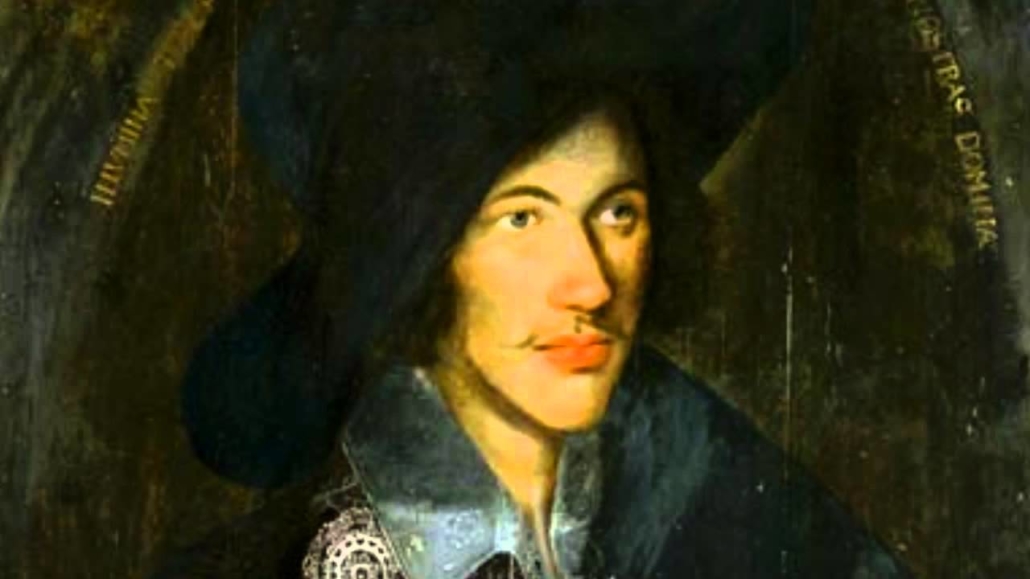

John Donne portrait

After his release he and Anne retired to the country where he took on work as a lawyer and they struggled financially, raising a large family.

In 1602 Donne was elected the Member of Parliament for Brackley. It was unpaid but it led to other things. He converted to Anglicanism, took orders and began to build a career as an Anglican clergyman. After many plaudits for his anti-Catholic pamphlets he ended up as the Dean of St Paul’s Cathedral in London, where he continued until the end of his life.

During all of that he was writing his poems. He is best known for his love poems and his religious poems, both filled with passion and enormous energy. The love poems were written to and about his wife, whom he adored. Any separation from her was painful and he wrote about that with great feeling.

One of his most famous quotes, indeed, one of the most famous in the English culture, is not from one of his poems but from a sermon from the pulpit of St Paul’s:

‘No man is an iland, intire of it selfe; every man is a peece of the Continent, a part of the maine; if a clod bee washed away by the Sea, Europe is the lesse, as well as if a Promontorie were, as well as if a Mannor of thy friends or of thine owne were; any mans death diminishes me, because I am involved in Mankinde; And therefore never send to know for whom the bell tolls; it tolls for thee…’

The great quality of Donne’s poems is that they speak out to and touch the feelings of readers of all generations in the most direct way. They are not big on imagery and there is no description. They are intellectual in that they employ intelletual rather than natural images and they use rational argument to develop their ideas. They use the language of something more like mathematics than what we would expect of poetry: for example, words like ‘thus,’ ‘therefore,’ ‘and so’ as the argument unfolds. They use as images, the most modern discoveries in astronomy, geography, physics and chemistry. And yet they are among the most emotionally moving poems written in English. An example is this poem, ‘A Valediction Forbidding Mourning’. In the poem he is saying goodbye to his wife as he sets out on a trip. He tells her not to make a fuss, not to cry and get upset. While he is away, he tells her, they will still be together because they are not really separating. No, they are two parts of one person and share one soul. He uses the image of a pair of compasses to describe this. She is the fixed point at the centre of the circle that represents his travelling. As he moves far away, she leans towards him, moving quietly, looking as though she isn’t moving at all as he moves in wide sweeps, always still attached to her. Then as he comes back she straightens up and meets him as they join physically. What little imagery there is is sexual. And it uses the image of the circle, which is not just mathematical but also the symbol of perfection and ending where one begins. It’s a remarkable poem and rightly very famous.

As virtuous men pass mildly away,

And whisper to their souls to go

Whilst some of their sad friends do say,

“Now his breath goes,” 1 and some say, “No.”

So let us melt, and make no noise,

No tear-floods, nor sigh-tempests move;

’Twere profanation of our joys

To tell the laity our love.

Moving of th’ earth brings harms and fears;

Men reckon what it did, and meant;

But trepidation of the spheres,

Though greater far, is innocent.

Dull sublunary lovers’ love

—Whose soul is sense—cannot admit

Of absence, ’cause 2 it doth remove

The thing 3 which elemented it.

But we by a love so far 4 refined,

That ourselves know not what it is,

Inter-assurèd of the mind,

Care less eyes, lips and hands 5 to miss.

Our two souls therefore, which are one,

Though I must go, endure not yet

A breach, but an expansion,

Like gold to airy thinness beat.

If they be two, they are two so

As stiff twin compasses are two;

Thy soul, the fix’d foot, makes no show

To move, but doth, if th’ other do.

And though it in the centre sit,

Yet, when the other far doth roam,

It leans, and hearkens after it,

And grows erect, as that comes home.

Such wilt thou be to me, who must,

Like th’ other foot, obliquely run;

Thy firmness makes my circle just,

And makes me end where I begun.

In his religious poems we feel that it is a real person speaking, someone of great intellectual and emotional power. The language is also very masculine, physical and robust. In a famous sonnet, expressing his commitment to the eternal life Christianity offers he addresses Death directly: ‘Death be not proud, though some have called thee mighty and dreadful: for thou art not so!’

When doubting his faith he calls on God to come to his aid, using the same tone: ‘Batter my heart three person’d God!’ His despair at finding himself in the arms of the Devil is such that he begs God to take him by force. He ends by saying that he will not be freed unless God rapes him.

In one of his love poems, ‘The Sunne Rising,’ annoyed at being woken so early while he feels his night of passion has been too short he scolds the sun:

‘Busy old fool, unruly Sun,

Why dost thou thus,

Through windows, and through curtains, call on us ?

Must to thy motions lovers’ seasons run ?’

Donne’s poems were not published in his lifetime but were circulated among his friends in manuscript form. We are fortunate enough to have several of them but there are many that have been lost. He was revived in the early 20th century by literary figures, including T.S. Eliot.

Read more about England’s top writers >>

Read biographies of the 30 greatest writers ever >>

Donne has been described candidly with illustrations.